CBD Wayfinding Signage

Wayfinding signage directs residents and tourists around the Town Square and beyond. As users explore what Bathurst has to offer, they will identify key heritage sites, navigate to museums and public facilities, and find shopping areas. The history on the signs will educate readers along their journey through the CBD, revealing the human stories underneath the built environment.

The CBD Wayfinding signage project forms part of Council’s Streets and Shared Spaces program aimed at revitalising the CBD. It was developed in consultation with local historians, community members and the Wiradyuri Traditional Owners Central West Aboriginal Corporation (WTOCWAC). The signage will be installed in a staged process, prioritising Wiradjuri stories first. Later installations will include stories about the Chinese of Bathurst, Irish colonial women, and our museums.

A note on the spelling of Wiradjuri/Wiradyuri

Council acknowledges that this signage project utilises two different spellings of the name of the local Aboriginal community, being Wiradjuri or Wiradyuri. In developing the content for the signs, the spelling was selected dependent on the source.

Council recognises that some Indigenous people may prefer the use of one spelling over the other. Out of respect for all, the use of both spellings are presented in this project.

Public Museums

Public Museums emerged in the early 19th century alongside the drive for technical education for the working classes. The learning philosophy of the day embraced that new knowledge was revealed not just though books but also though science, experimentation, and the study of objects. From the 1830’s settlements in the NSW colony established Mechanics Institutes later to be called School of Arts devoted to adult (working class) education. The NSW Government matched community fund raising however the School of Arts were community-led organisations and often included ‘Museums’ and ‘libraries’ with a variety of books, specimens and collections borrowed or donated from within their communities.

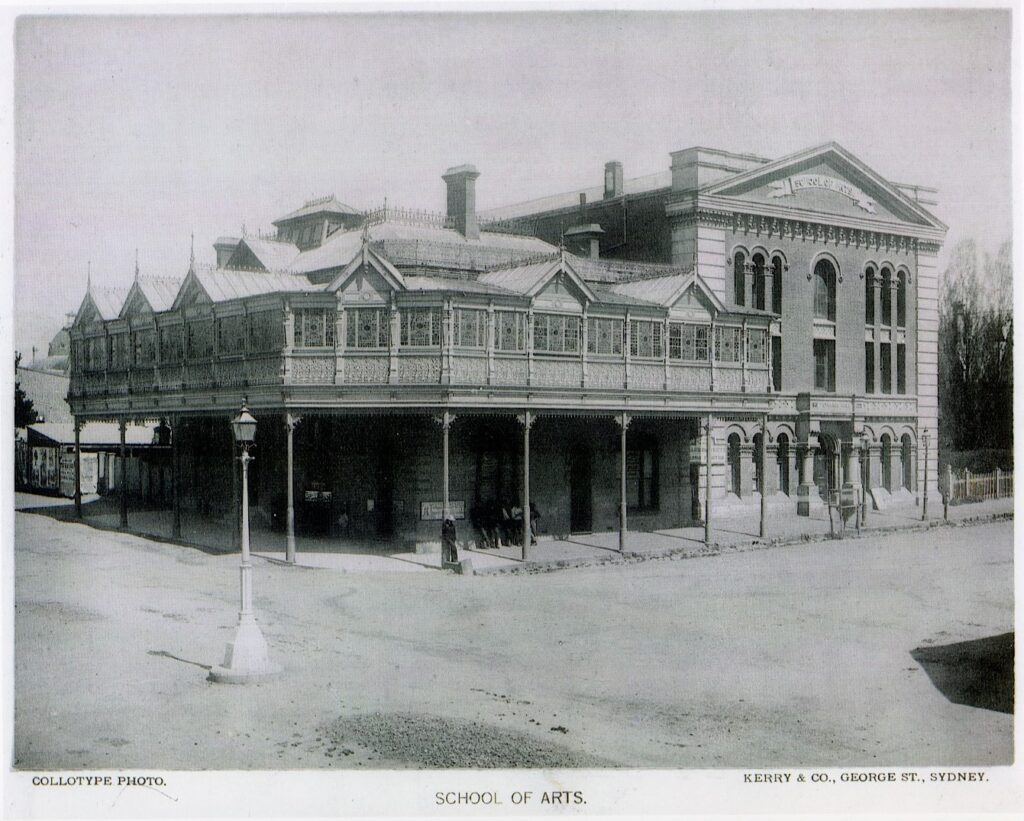

Bathurst first formed a Mechanics institute in the 1840’s but it wasn’t until the late 1850’s that it began to have broad support. By the 1860’s it was renamed School of Arts and had established buildings on the corner of Howick and William Streets. By the 1890’s following lobbying from the Bathurst Community, and the School of Arts Board in particular, the colonial government called for tenders for the construction of a ‘technological college’ and a ‘technological museum’.

What is now known as the former TAFE building is the result, the adjacent ground floor corner was a public museum. The building opened in 1897 and the Museum, with its own entrance off William Street was open soon after. Its initial collection was a combination of the School of Arts mineral specimens and the collection from a Community Museum housed on Keppel Street. The collection included a stuffed lion, various minerals, fine porcelain and textiles from all over the world, latter it included a Cobb and Co coach. The Museum closed in the late 1970s and anything of value in the collection was transferred to the NSW Powerhouse Museum. The rest found its way to the Bathurst tip (surprised locals found the lion there) and the Bathurst Historical Society Museum.

A Bathurst Councillor (Les Wardman) intervened in relation to the Cobb and Co coach, and with the assistance of Premier Neville Wran, received approval for Bathurst Council’s ownership of the Coach. The coach is listed as both a local and state heritage item and has been fully restored. It can be viewed at the Bathurst Information Centre and is one of a suspected six remaining.

Bathurst operates a diverse group of local Museums. Each has unique and extraordinary collections to explore though tours, learning programs, and continually evolving exhibitions and events:

- Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum

- National Motor Racing Museum

- Bathurst Rail Museum

- Chifley Home and Education Centre

A number of community museums also operate including Bathurst District Historical Society Museum and the National Trust Miss Trail’s House.

Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum (Provided by Bathurst Regional Council)

School of Arts (right), formerly located near corner of William and Howick Streets. (Provided by Bathurst Regional Council)

Cobb & Co

A diversity of transport services was developed though the 19th and 20th centuries to deliver people, products and services to the new rural settlement areas including private horse stage coaching. In 1862, Cobb and Co shifted their headquarters to Bathurst to merge with the existing Western Stage Co after initially establishing in Victoria. At Bathurst, Cobb & Co expanded rapidly with their comprehensive approach, reliability, speed, comfort and for their transportation of gold and mail. The company had the most successful coaching system in the world based on distances travelled and length of time of operation.

The New Yorker, James Rutherford (Executive Managing Director), drove the first coach at Bathurst. Under his leadership, the firm became vertically integrated, building factories to build their custom ‘Australian’ coaches utilising Australian timbers (blue gum and ironbark) and adapted for the harsh terrain. The Bathurst Coach Factory was a major employer. It was there that a new form of support under the coaches was developed; leather thoroughbraces cradled the passenger seat and took the ‘jolt’ out of the ride.

Cobb & Co also acquired pastoral properties to breed their ‘Coacher’ horse and to produce fodder and grain. Contrary to popular belief, the Coacher was not dominated by draught breeds (such as Clydesdale) but was a mix of trotter, draught horse, thoroughbred and later the Arabian. These horses were 14 to 16 hands high, wide-chested, strong, and muscular with fine legs, speed and stamina. Horses were changed frequently about every 25km to 30km so as to maintain coach speed. Many horses in today’s racing industries descend from Cobb & Co bloodstock.

The Cobb & Co experience was an egalitarian one. In 1882, Cobb & Co introduced the 8-hour day for their workers much to the consternation of other employers in town. The Coaches were known to carry a multitude of nationalities to the goldfields, transported rich and poor in one carriage, employed Aboriginal people and women, and patronised hotels owned by women and men from all nations.

Mrs Byrnes was the mother of 13 children and drove a coach between Canowindra and Orange in her spare time, her children (when there was room) riding along with her. Legend has it she saw a bushranger ambush ahead and, afraid for her children’s safety, told them to disembark and hide in adjacent bush. She drove up to the ambush alone, then returned after the holdup to collect her children.

An original Cobb & Co coach from the Sofala to Bathurst route in the Bathurst Red and Gold colours can be viewed at the Bathurst Visitor Information Centre.

Factory – workers at Bathurst Factory (Source: Cobb & Co Heritage Trail Bathurst to Bourke by Dianne de St. Hilaire Simmonds, 1999.)

Coach (Source: Cobb & Co Heritage Trail Bathurst to Bourke by Dianne de St. Hilaire Simmonds, 1999.)

‘Peace Celebrations’ in Bathurst, late 1918. From 1876-1911, Cobb & Co leased the School of Arts building on the corner of Howick an William Street (right). To the left is the former Bank of Australiasia and the former Technical College. Source: BDHS.

Bathurst Rebellions

From 1821 the new Governor of NSW, Sir Thomas Brisbane, ‘privatised’ the convict system and ended the former Governor Macquarie’s limit on inland settlement. This led to an explosion in land grants to the Colonial Pastoralist elite, keen for more land and free convict labor to work them. Convicts were assigned to the road gangs under military supervision prior to being assigned to a master. Their conditions worsened. They faced reduced rations, harsher punishment, and raids by Wiradjuri Warriors whose land had been usurped. A ticket of leave was offered to convicts as motivation, though if earned, they would still be required to live and work in the district, report to a magistrate, and attend church regularly. However the terms by which a ticket of leave was earned was not only unclear to convicts but practically unachievable.

In November 1829, John Lipscombe gave his convict of only two years, Ralph Entwistle, one last task before being granted a ticket of leave. It was unusual for Entwistle to be promised a ticket of leave so early. In reality, he was ineligible. Nevertheless, he was to transport a load of merino wool to a market in Sydney. On the first day of the journey, Entwistle and three other men skinny dipped in the Macquarie River/Wambuul to relieve themselves from the hot weather. They were spotted by the entourage of the passing Governor Darling. Entwistle received a public flogging of 50 lashes on charges of ‘causing an affront to the Governor’ despite the Governor never having witnessed the skinny dipping himself. Entwistle was arrested, his ticket of leave nullified by Libscombe, and was trialed under authority of a Bathurst Magistrate who had competing merino wool interests in the district. The wool being transported was confiscated.

Resentful of his poor treatment from his master and authorities, in September 1830, Entwistle absconded from Libscombe’s farm, Stowford, with a band of nine convicts who became known as the ‘Ribbon Boys’ (aka the Ribbon Gang). They roamed the region collecting members and stealing food, guns, horses, ammunition. At one stage they rumoured to be 80 people strong. Governor Darling, fearing others would also rise up, sent the 39th Regiment from Hyde Park barracks to take action against the rebels. Three bloody battles followed with the ‘core’ Ribbon Gang eventually being captured in the Abercrombie Caves.

The captured Ribbon Gang members were the first to be trialed under a freshly minted ‘Bushranger’s act’ (“Robbers and Housebreakers Act” 21 April 1830). On 2 November 1830, ten men, including Entwistle, were hung on custom gallows specially erected in the vicinity of what is now known as Ribbon Gang Lane. It was the largest public mass hanging in NSW history.

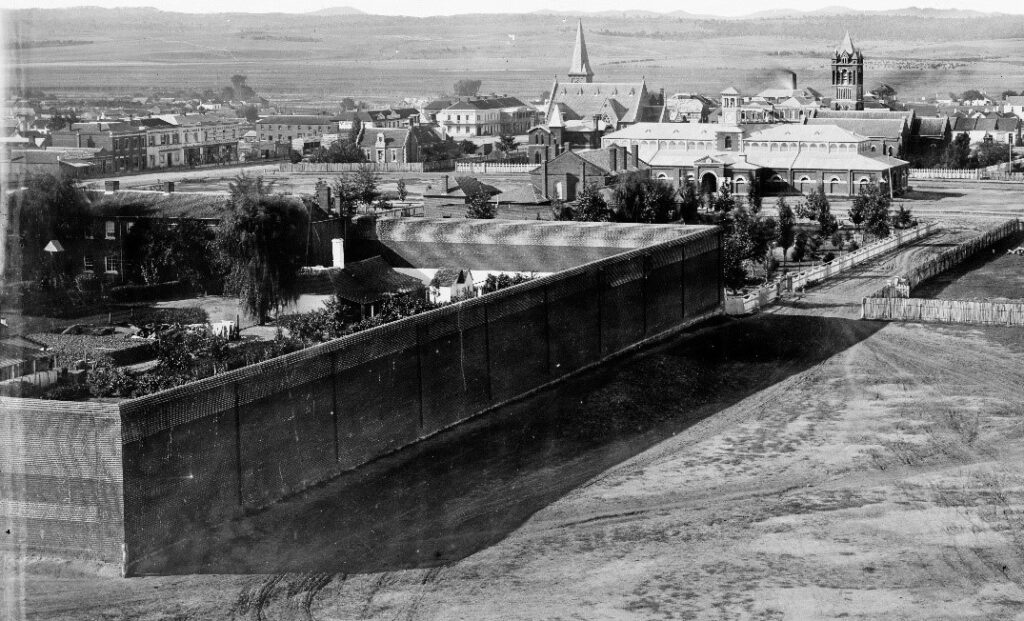

Executions in the CBD continued within the brick walls built around the former gaol, located on what is now Machattie Park. The walls stacked approximately 5m high limited public spectatorship.

Part of panorama of Bathurst, looking north and taken from tower of the Catholic Cathedral, 1870-1875. Source: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

References:

Bialowas, H 2010, Ten Dead Men: A Speculative History of the Ribbon Gang, CSU Print, Bathurst.

Shaw, I.W 2020, A Concise Guide to the Bathurst Rebellion, [https://aguidetoaustralianbushranging.com/2020/10/30/a-concise-guide-to-the-bathurst-rebellion/], A Guide to Australian Bushranging, accessed 14 February 2023.

There’s a reason why the Wiradjuri people avoid the Abercrombie caves. A dreamtime story tells of a dark tale of Mirragen, the cat-man. He was renowned as a great fisherman and used his skill and knowledge of spells to catch his prey. For some time, he had only been able to catch small fish in the rivers near to his home. Mirragen was not satisfied with this and so he set out in search of bigger and better prey.

In a deep hole at the junction of two mighty rivers lived a monster that was half fish and half lizard. His name was Gurangatch. Mirragen arrived at the deep hole and, peering into its depths, saw Gurangatch. The cat-man cast spells to try and catch Gurangatch but the monster was too clever and stayed at the bottom of the pool where the spells would not reach.

The next day, Mirragen tried his magic again but this time he also poisoned the water with tincture of bark. Gurangatch began to float to the surface, but just in time he realised what was happening to him. He knew he had to do something or he would be caught.

The only way that he could escape was to burrow through the solid rock. When Mirragen saw that Gurangatch had escaped, the chase began. As Gurangatch burrowed, he created new rivers and the tunnels in the rock became the Wombeyan Caves and the Jenolan Caves. Despite enlisting help from the Bird-men, Mirragen was not able to capture Gurangatch.

In Wiradjuri oral history, Abercrombie Caves was created by Gurangatch being relentlessly hunted by Mirragen. It is a place that is avoided, respecting its dark creation history.

Source: Wiradjuri Traditional Owners Central West Aboriginal Corporation elders, 2023.

K Keck, 1991, Cave Chronicles.

Blue Bee Mural

Birrunga Wiradyuri with Kane Brunjes, Stevie O’Chin, and the Bathurst Wiradyuri Elders Blue Banded Bee Creation Story 2022, 6 m x 15 m, Post Office Building, 230 Howick St, Bathurst.

Birrunga Wiradyuri’s mural tells the creation story of the blue banded bee as told to him by his Elders:

The bees come from gibirrgan (the southern cross). They fall down to earth from these stars and when they first begin falling from the sky, they are bright white balls of light. As they fall and get closer to earth, they become glowing golden balls and when those golden balls land on earth they become our bees.

The important role the blue-banded bee plays in the ecosystem holds special significance for the Wiuradyuri. Other elements of the mural design, such as the white five-lined circular motif representing a Songline, explore the five aspects of the Wiradyuri central lore of Yindyamarra: to do slowly – to be polite – to be gentle – to honour – to respect.

Blue banded bees (Amegilla) are endemic to Australia, with eleven varieties found in all states and territories except Tasmania. These beautiful bees are recognised for the bold blue stripes on their abdomens, five on the males and four on the females.

Blue banded bees are important pollinators. Their long tongues allow them to access deep pollen reservoirs. They are also buzz pollinators which means that they can grasp flowers and vibrate them to shake pollen loose. The flowers of many of our native plants, and some crop plants such as tomatoes, are specially adapted to be pollinated by buzz-pollinators.

Blue banded bees are known as stingless bees. In many ways the benign nature of the blue banded bees embodies the strengths of the Wiradyuri lore of Yindyamarra. The bees in this mural are stylised and have specific symbolism in their design.

Artwork design was undertaken in consultation and collaboration with the Bathurst Wiradyuri Elders, the Traditional Custodians of the Bathurst region. The mural was painted by Birrunga Wiradyuri with Kane Brunjes and Stevie O’Chin, young First Nations artists who Birrunga mentors through the Birrunga Gallery’s three-year Cultural Creative Residential program.

Birrunga Wiradyuri is a Wiradyuri man. He is the founder and principal artist of the multi award winning Birrunga Gallery and Dining in Brisbane’s CBD and is dedicated to fulfilling his cultural responsibilities, following, and practicing the central Wiradyuri law of Yindyamarra. Birrunga is a practicing visual artist whose narrative works explore the spirituality of the Wiradyuri people, in historical and contemporary contexts.

Birrunga has undertaken numerous public art commissions, and has exhibited widely, including a solo exhibition at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery in 2020. Birrunga participated in the Australia Council’s Custodianship Program in 2020. Through his work at the Birrunga Gallery he mentors young First Nations artists through the Birrunga Gallery’s three-year Cultural Creative Residential program.

Kane Brunjes is a Gunggari, Kabi Kabi man practicing in both public and gallery realms. Through his art practice Brunjes aims to solidify and represent a visual portrayal of how he views and reacts to the environment surrounding him with consideration to history and story. Now working exclusively with Birrunga Gallery he continues to develop these core foundations with a guided lens of expertise. Brunjes is the inaugural participant in Birrunga Gallery’s 3-year Cultural Creative Residential program.

Stevie O’Chin is an Aboriginal artist of the Kabi Kabi, Waka Waka & Koa tribe on her father’s side, and Yuin Nation on her mother’s side. Her paintings are inspired by her surroundings and the stories told by her parents and family elders. Stevie hails from a large family; many whom are artists from both her parents’ side. She was influenced from a young age and has learnt to paint from watching her family members. She is now carving her own path and has grown into an accomplished artist in her own right. O’Chin is the second participant in Birrunga Gallery’s 3-year Cultural Creative Residential program.

Irish Famine Women of Colonial Bathurst

Irish women found their way to Bathurst in the 1850s through an emigration scheme designed to move orphan girls from the over filling Irish Poor workhouses to the Australian colony. The selection process was strict. The girls were generally of ages ranging between 14-18 and were required to have a certificate of ‘unblemished moral character’ from the Master and Matron of their workhouse. Of the 3514 girls, records show that nearly 10% could read and write, 32% could read only and 40% could neither read nor write. Embarking on the 3–4-month voyage, they could only bring with them a small box in which to keep their clothes and small items.

Despite the apparent desire for women as wives, mothers and servants, the specially selected Irish Catholic girls entered a political climate in Australia where the sympathy for famine-ravaged Ireland was not enough to overcome anti-Irish Catholic sentiment. Upon arrival, the girls were described as a ‘useless, incompetent horde of ignorant children’, an affront to the colony.

In Bathurst, the Irish famine girls were housed in the vacant military barracks in the old gaol building. Before marriage, they were subject to relentless drudgery and labour-intensive work as servants to married women of the emerging middle class. Annual wages were £5-11 ($1,501 – $3,302.27), depending on age and skill. On average the Irish girls were married within 3 years of having arrived in the colony. If not already indentured to Bathurst, for some, marriage was the cause to be relocated. For 55 girls, their lives in Bathurst began due to being banished from Sydney for bad behaviour. Approximately 185 Irish girls are recorded to have spent time in Bathurst, if not having lived out the rest of their lives in the town or surrounds.

Religious bigotry aside, many ‘delinquent’ girls became well established and highly respected in their communities. If the dangers of childbirth were survived, the women typically had large families; on average 8 children and one woman had as many as 15 children. Juggling demanding domestic duties with entrepreneurship, some Irish women ran boarding houses, hotels and inns, were employed as teachers, and, though it is not well documented, assisted their husbands as successful bakers, builders or shoemakers. Mary Ann Adderly, banished to Bathurst for neglect of duty and disobedience, married Matthew Rose who built The Royal Hotel in Milthorpe and held over 60 acres of land. After his death in 1889, and for the proceeding 20 years until her own death, Mary Ann was a widow, hotelkeeper, mother to 13 children and grandmother to 96 children. Her estate was valued at £1780, or approximately $472,593.11 in 2023.

Photo believed to be of Mary Ann Adderley, circa 1875. (Source: https://studylib.net/doc/18826626/read-her-story—irish-famine-memorial)

Reference:

L.G. Blair and P. McIntyre 2019, ‘Fair Delinquents’? Irish Famine Orphans of Colonial Bathurst and Beyond’, Eitherside Publications, Robina.

The colony was not receptive of the Irish famine girls. Fearful of the colony being overrun by Catholics, the girls faced severe religious bigotry for the fault of not being raised as Protestants. Their skills were immediately denounced, perhaps rightly so as the colonists had unrealistic expectations of the domestic skills of rural Ireland girls.

Bathurst and surrounds seemed to suit the Irish famine girls in comparison to the city. The girls showed a willingness to learn and to overcome the stereotypes placed upon them, however servantry or marriage did not keep them safe from experiencing domestic abuse, sexual assault, or the horror of predeceasing their own children. In 1869, Ellen Burke lived in a tent with her husband and 8 children. Her eldest daughter, Ellen, was nearly 12 when she poisoned herself with strychnine and arsenic. Convulsing, she refused to be touched and when asked why she poisoned herself, she replied that if she was flogged, she couldn’t live.

Bridget Hammond, an orphan servant aged 17 who could neither read nor write was repeatedly raped at her workplace by a convict also in service to the home. Shame prevented her from making any complaint to her employees. The perpetrator, Henry Gratton, appears to have been committed for the rape but as Bridget had not reported the incidents, there was ‘insufficient’ evidence to prosecute. The account of Gratton’s bad character was enough to cancel his ticket of leave. Hammond was then sent to the Bathurst immigration depot with one last chance to find a place to work, an attitude contrary to the duty of care the government had to the girls of the immigration program.

Some lived up to the ‘delinquent’ stereotype. Jane Cunningham was seen in the Bathurst court for taking ‘sundry liberties with the Queen’s English not permitted by the Vagrancy Act’. The case was dismissed as a neighbourly dispute. Mary Anne Duffy, at 22, married her husband William Connor of the Sofala goldfields, aged 44, and after three weeks of marriage abandoned her husband and was charged in Bathurst with vagrancy. She was routinely reported in the press for obscene language, vagrancy, and drunkenness.

Mary Daniels was banished to Bathurst and soon after her marriage at 17, abandoned her husband with Margaret Parsons, also 17. The two were caught and charged with having stolen £265. Margaret claimed ignorance of the theft and the money was not found with Mary’s belongings. The case was dismissed. Upon being told she was to return with her husband, Mary begged the court to send her to gaol as she preferred it to returning with her husband, was at first refused, and upon reapplying received sympathy and could exit via a separate door to her husband. It is not known what happened to Mary Daniels. Her husband died 8 years after this incident.

Reference:

L.G. Blair and P. McIntyre 2019, ‘Fair Delinquents’? Irish Famine Orphans of Colonial Bathurst and Beyond’, Eitherside Publications, Robina.

The Chinese of Bathurst

Chinese people have a long and rich history in Bathurst. A small number of Chinese indentured labourers in the Bathurst district pre-dated the large number of Chinese gold-seekers who came to the goldfields around Bathurst in 1858. Chinese gold-seekers were a dominant presence on some fields. According to the NSW Census of 1861, 1877 men in the Sofala Registry District were Chinese, equating to over half of the male population of Sofala. The co-operative methods and success of Chinese miners on the goldfields were at times resented by European miners, resulting in clashes on goldfields around Bathurst, most notably at Native Dog Creek near Rockley in 1861 and at Napoleon Reef in 1866. Though there were no Chinese-born women living on the goldfields, there were marriages between Chinese men and European women.

In the 1870s, Chinese stores began opening in Bathurst and Chinese began establishing market gardens where they grew and supplied vegetables to residents of the district. Market gardens in Bathurst were on the alluvial flats of the Macquarie River Wambuul at Esrom, Kelso and along the Vale Creek. Chinese market gardeners leased land from landowners such as F.B. Suttor and later Robert Gordon Edgell at Bradwardine, or worked successful share-farming agreements with European growers. Market gardeners on the Campbells River, at White Rock and Lagoon brought their vegetables into Bathurst on the weekends to sell door-to-door and stayed in rented premises in the Chinatown area of Stewart, Howick, Rankin and Durham Streets.

The arrival of rail in Bathurst in 1876 gave access to the Sydney market. Newspapers reported hundreds of tonnes of Chinese-grown cabbages, potatoes and onions transported by rail to the Haymarket. In the era before irrigation, Chinese growers pioneered commercial vegetable production in Bathurst. Their vegetables dominated the Vegetable Produce awards in the Bathurst Show from the mid-1880s. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s William Owen won prizes for his vegetables at the Bathurst Show. Charley Owen (On Won) and his son William occupied 75 acres at White Rock in 1920 before growing vegetables in Kelso.

The introduction of White Australia legislation that prohibited migration, naturalisation and land ownership contributed to the decline of the Chinese community in Bathurst. The demolition of the Chinese Masonic Lodge in 1953 signalled the end of Bathurst’s Chinatown. Nonetheless, descendants of this early Chinese community continue to live in Bathurst today.

Source: Juanita Kwok, 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

Charley and Lucy On Won (Owen) and their family at White Rock. Photo courtesy of Debbie Cannon-Clark.

The backyard of the Chinese Masonic Lodge in Bathurst, established in 1921. It stood on the corner of Rankin and Durham Street and was demolished in 1953. Photos taken circa 1947-1952, courtesy Tony Bouffler.

巴打士的华人

(「巴打士」是英文镇名Bathurst的中文音译,也曾译作「巴打池」、「巴打市」、「巴打时」等。本地华人早于淘金热时期已开始使用「巴打士」这个译名,二十世纪上半页本地华文报纸也会这样称呼Bathurst。清代进士魏源《海国图志》1852年版本的〈澳大利亚专图〉似乎用了「巴嗒士」这个发音十分近似的音译。中国官方近来为它起了个新名叫「巴瑟斯特」,也指同一个镇。这篇本地短史谋求原汁原味,各城乡市镇尽量使用它们的旧名,也就是本地以及澳洲华人史上用的名称。)

华人在巴打士(Bathurst)有着悠久、丰富多彩的历史。1858年,大批的华人淘金者来到了巴打士附近一带的金矿区(当时叫「金山」),但其实之前已经有少量受雇为契约劳工的华人在该区聚居。在某些金矿区中,华人淘金者人数占大多数。例如,根据鸟修威州府(新南威尔士殖民地)1861 年的人口普查资料,在索法拉登记区(Sofala Registry District) 中,华人男性有 1,877 人,占索法拉男性人口一半以上(据考,索法拉镇的中文旧名是「都仑正埠」,似乎是本着该地河名 Turon 而起的)。在淘金方面,由于华人采用互相合作的方式,加上他们的淘金成绩斐然,因此不时惹来欧洲淘金者的嫉妒,导致在巴打士周边金矿区发生了一些冲突,其中最引人注目的,是发生于 1861 年在 Rockley 附近的 Native Dog Creek (「丁狗冲」)和 1866 年在 Napoleon Reef(「拿破仑金矿地」) 这两起冲突。金矿区没有华裔女性居住,然而华人男性与欧洲女性之间互相通婚,可也确有其事。

在 1860 和 1870 年代期间,华人店铺开始在巴打士出现,华人也同时着手创立菜园,種植各種蔬菜以供應区內居民所需。当时巴打士的菜园一般位于 Esrom、Kelso 以及沿着 Vale Creek(「山谷冲」)靠近 Macquarie/Wambuul(麦瓜厘) 河一带的冲积平原上。华人菜农从像是 F.B. Suttor 和后来的 Robert Gordon Edgell 这些地主那里租用土地,在 Bradwardine 種植,或与欧洲农民成功签订合作種植协议。在 White Rock 和 Lagoon 靠近 Campbells 河的菜农到了周末,会把蔬菜带到巴打士挨家挨户兜售,他们也会在 Stewart 街、Howick 街、Rankin 街和 Durham 街一带的唐人街租地方歇脚。

1876 年巴打士终于通上了铁路,让当地市民能夠更方便往来雪梨市場(雪梨即悉尼;据考,悉尼一名虽然起得还早,但是澳洲华人以前通用雪梨一名)。当时报纸报导了数百吨由华人種植的捲心菜、土豆和洋葱利用铁路运往希孖结菜市(雪梨大菜市 Haymarket)的情况。早于还未采用机械化灌溉系统的时代,巴打士华人種植者已开创了蔬菜生产商业化的先河。从 1880 年代中期起,他们的蔬菜在巴打士农展会(Bathurst Show)上,开始获得大多蔬菜产品奖项。例如从 1920 年代至 1930 年代初期,罗安明(Charlie Owen)先生的儿子威廉·欧文(William Owen) 在巴打士农展会上多次获得蔬菜奖项。据研究显示,在 1920 年,罗安明和威廉·欧文父子俩在 White Rock 占有 75 英亩的土地,后来他们迁往 Kelso 種植蔬菜。

随着澳大利亚实施白澳政策,包括禁止华人移民、入籍以及拥有土地,巴打士华人社区逐渐式微。1953 年巴打士致公堂(Chinese Masonic Lodge)遭到拆除,这标志着巴打士唐人街的没落。然而这个早期华人社区的后代,至今仍然居于巴打士。

资料来源:Juanita Kwok(郭思恩博士), 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

罗安明夫妇(查理和露西·欧文Charlie and Lucy Owen) 以及他们在 White Rock 的家人全家合照。照片由 Debbie Cannon-Clark 提供。

巴打士华人合照。后排中间是西人比尔·布夫勒(WT/Bill Bouffler),他在佐治(乔治)街布夫勒兄弟肉店当屠夫。后排右一一位相信是Jimmy Jong,在他和比尔·布夫勒前面中间站着的,是 Wong Youk。其他人姓名不詳。拍摄地点是 Rankin 和 Durham 两条街交界处的澳洲华人致公堂后院。摄于 1947 至 1952 年左右,由 Tony Bouffler 提供。

Attribution for translation:

温楚良(Aaron Wan)先生翻译,林雍坣(Ely Finch)先生提供中文旧地名等。

巴打士的華人

(「巴打士」是英文鎮名Bathurst的中文音譯,也曾譯作「巴打池」、「巴打市」、「巴打時」等。本地華人早於淘金熱時期已開始使用「巴打士」這個譯名,二十世紀上半葉本地華文報紙也會這樣稱呼Bathurst。清代進士魏源《海國圖志》1852年版本的〈奧大利亞專圖〉似乎用了「巴嗒士」這個發音十分近似的音譯。中國官方近來為它起了個新名叫「巴瑟斯特」,也指同一個鎮。這篇本地短史謀求原汁原味,各城鄉市鎮盡量使用它們的舊名,也就是本地以及澳洲華人史上用的名稱。)

華人在巴打士(Bathurst)有著悠久、豐富多彩的歷史。1858年,大批的華人淘金者來到了巴打士附近一帶的金礦區(當時叫「金山」),但其實之前已經有少量受僱為契約勞工的華人在該區聚居。在某些金礦區中,華人淘金者人數佔大多數。例如,根據鳥修威州府(新南威爾士殖民地)1861 年的人口普查資料,在索法拉登記區(Sofala Registry District) 中,華人男性有 1,877 人,佔索法拉男性人口一半以上(據考,索法拉鎮的中文舊名是「都崙正埠」,似乎是本著該地河名 Turon 而起的)。在淘金方面,由於華人採用互相合作的方式,加上他們的淘金成績斐然,因此不時惹來歐洲淘金者的嫉妒,導致在巴打士周邊金礦區發生了一些衝突,其中最引人注目的,是發生於 1861 年在 Rockley 附近的 Native Dog Creek (「丁狗沖」)和 1866 年在 Napoleon Reef(「拿破崙金礦地」) 這兩起衝突。金礦區沒有華裔女性居住,然而華人男性與歐洲女性之間互相通婚,可也確有其事。

在 1860 和 1870 年代期間,華人店鋪開始在巴打士出現,華人也同時着手創立菜園,種植各種蔬菜以供應區內居民所需。當時巴打士的菜園一般位於 Esrom、Kelso 以及沿着 Vale Creek(「山谷沖」)靠近 Macquarie/Wambuul(麥瓜釐) 河一帶的沖積平原上。華人菜農從像是 F.B. Suttor 和後來的 Robert Gordon Edgell 這些地主那裡租用土地,在 Bradwardine 種植,或與歐洲農民成功簽訂合作種植協議。在 White Rock 和 Lagoon 靠近 Campbells 河的菜農到了週末,會把蔬菜帶到巴打士挨家挨户兜售,他們也會在 Stewart 街、Howick 街、Rankin 街和 Durham 街一帶的唐人街租地方歇腳。

1876 年巴打士終於通上了鐵路,讓當地市民能夠更方便往來雪梨市場(雪梨即悉尼;據考,悉尼一名雖然起得還早,但是澳洲華人以前通用雪梨一名)。當時報紙報導了數百噸由華人種植的捲心菜、土豆和洋蔥利用鐵路運往希孖結菜市(雪梨大菜市 Haymarket)的情況。早於還未採用機械化灌溉系統的時代,巴打士華人種植者已開創了蔬菜生產商業化的先河。從 1880 年代中期起,他們的蔬菜在巴打士農展會(Bathurst Show)上,開始獲得大多蔬菜產品獎項。例如從 1920 年代至 1930 年代初期,羅安明(Charlie Owen)先生的兒子威廉·歐文(William Owen) 在巴打士農展會上多次獲得蔬菜獎項。據研究顯示,在 1920 年,羅安明和威廉·歐文父子倆在 White Rock 佔有 75 英畝的土地,後來他們遷往 Kelso 種植蔬菜。

隨着澳大利亞實施白澳政策,包括禁止華人移民、入籍以及擁有土地,巴打士華人社區逐漸式微。1953 年巴打士致公堂(Chinese Masonic Lodge)遭到拆除,這標誌着巴打士唐人街的沒落。然而這個早期華人社區的後代,至今仍然居於巴打士。

資料來源:Juanita Kwok(郭思恩博士), 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

羅安明夫婦(查理和露西·歐文Charlie and Lucy Owen) 以及他們在 White Rock 的家人全家合照。照片由 Debbie Cannon-Clark 提供。

巴打士華人合照。後排中間是西人比爾·布夫勒(WT/Bill Bouffler),他在佐治(喬治)街布夫勒兄弟肉店當屠夫。後排右一一位相信是Jimmy Jong,在他和比爾·布夫勒前面中間站着的,是 Wong Youk。其他人姓名不詳。拍攝地點是 Rankin 和 Durham 兩條街交界處的澳洲華人致公堂後院。攝於 1947 至 1952 年左右,由 Tony Bouffler 提供。

Attribution for translation:

温楚良(Aaron Wan)先生翻译,林雍坣(Ely Finch)先生提供中文旧地名等。

The Chinese of Bathurst – William Beacham

From the 1850s-1950s, Howick Street to Rankin and along to Durham Street was an area known as Chinatown, consisting of stores, family residences and rented rooms for market gardeners who brought their vegetables in on weekends. At 105 George Street (corner of The Bolam Centre) was Beacham’s store. The proprietor, William Beacham (Chinese name unknown) was born in Amoy, China in 1835. Aged 17, he arrived at Port Jackson on the Royal Saxon in 1853, one of 304 men from Amoy imported as labourers by Robert Towns. It is likely that Beacham was amongst 44 of the men sent to work for the Colonial Gold Company on the Western Goldfields. In 1858 Beacham was a gold miner in Sofala and later a storekeeper and interpreter there. In 1864 he married Agnes Fanning but after her death, moved to Bathurst with his daughter, Margaret. Beacham married Honora Johnston in 1883 and the couple had five children. William and Honora’s relationship is an example of supportive relationships which existed between Chinese men and European women despite the racist stigma of associating with Chinese men.

Beacham was elected to the Bathurst Hospital Committee in 1884, won prizes at the Bathurst Show in 1885 and 1895 for the fat pigs he raised and for the tobacco and vegetables he grew. He combined store-keeping with a forty-year career as a Chinese court interpreter at Bathurst. He was well respected in the community; appreciated for his interpreting skills despite being a Hokkien speaker amongst a majority of Cantonese speakers.

He publicly defended the Chinese community in 1891, after the National Advocate published a letter allegedly written by a European woman imprisoned against her will in an opium den in Bathurst. In a letter to the editor, he wrote:

the letter and also the article are false from beginning to end – no such woman ever existed as the one referred to. I am acquainted with all the women in the district, and must say that the article is a gross libel upon the whole of my countrymen.

Made a naturalised British subject in 1872, William Beacham lived through the eras of indentured labour, the gold rushes, the rise of Chinese market gardening and the introduction of White Australia policies. After his death in 1909, his youngest son Norman ran the store as a fruit shop then tobacconist until 1929. Norman married Emily Jones in 1913, but knowledge of the family’s Chinese heritage was hidden from the children, only to be rediscovered by William’s great-grand-daughter Wendy Pickering and other family members.

Source: Juanita Kwok, 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

Aerial view of Bathurst, New South Wales, 9 June 1933, showing location of Beacham store, Fairfax archive of glass plate negatives. Source: Trove. (Access original https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-162357694/view)

Norman Beacham (right) with his son Ross (left). Norman operated Beacham & Sons at 105 George Street. Photograph courtesy of Wendy Pickering.

There are no surviving photographs of William Beacham.

Chinese tobacco plantation, Bathurst, John Henry Harvey, 1855-1938. Photograph courtesy of State Library of Victoria. The site has been identified as Mt Pleasant, near Abercrombie House.

从 1850 年代到 1950 年代,由 Howick 街到 Rankin 街,再到 Durham 街,该范围称为唐人街,那里有商店、住宅和供菜农租用的房间,这些菜农周末会把蔬菜运到镇里出售。华人比彻姆的商店位于佐治(George)街 105 号(即 Bolam Centre 角落) ,店主威廉·比彻姆(William Beacham,中文名字不詳)1835 年出生于大清国厦门府一带。1853 年比彻姆以 17岁之龄,乘坐 Royal Saxon「皇家撒克逊号」抵达 Port Jackson(杰克森港,即悉尼港)。当时,船上有 304 名由罗伯特·唐斯(Robert Towns)从厦门载运前来的劳工,比彻姆就是其中一人。及后有 44 人调派到 Western Goldfields(西部金矿区)替 Colonial Gold Company「殖民地金矿公司」工作,比彻姆很可能身居其列。比彻姆于 1858 年在索法拉(旧名「都仑埠」)做金矿工,后来又在那里开店铺、做翻译。1864 年,他与 Agnes Fanning「阿格尼丝·范宁」结婚,在她去世后,便带着女儿 Margaret「玛格丽特」迁往巴打士。1883 年,比彻姆与 Honora Johnston「霍娜拉·约翰斯顿」结婚,夫妇育有五个孩子。威廉·比彻姆和霍娜拉两人的关系正好说明,尽管当时与华人男性交往或者带有種族主义的恥辱感,但是华人男性与欧洲女性之间并非没有恩愛相守的例子。

比彻姆于 1884 年获选入巴打士医院委员会。他在 1885 年和 1895 年凭借自己饲养的肥猪以及種植的烟草和蔬菜,在巴打士农展会上赢得了一些奖项。比彻姆除了经营商店外,还同时在巴打士担任了 40 年的华人法庭翻译员,广受当地社群尊重和爱戴,另一方面,尽管他的母语是闽南语,而当地大多数人说的是粤语,但他们都十分赞赏其翻译技能。

1891年,当地报纸《National Advocate》刊登了一封据称是一名欧洲妇女撰写,讲述自己曾被关押在巴打士一个鸦片窝中的信件后,比彻姆公开为华人社区辩护。他在《给编辑的信》中宣称:

那封信件和那篇文章从头到尾都是虚假的。该区妇女我都认识,那个所谓涉事的女人根本不存在。我还必须指出,这篇文章对我全体同胞构成了严重的诽谤。

威廉·比彻姆曾于 1872 年入籍成为英国公民,他经历了契约劳工时代、淘金潮、华人菜园的兴起以及白澳政策的推行。1909 年比彻姆去世后,他的么子 Norman「诺曼」接手经营其商店,首先是水果店,后改为烟草店,一直经营至 1929 年。诺曼于 1913 年与 Emily Jones「艾米莉·钟斯」结婚,但他们从不向孩子透露家族成员带有华人血統一事。这个事实后来由比彻姆的曾孙女 Wendy Pickering「温蒂·皮克林」和其他家人所发现。

资料来源:Juanita Kwok(郭思恩博士), 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

鸟修威省(新南威尔士州)巴打士的鸟瞰图。摄于 1933 年 6 月 9 号,显示了比彻姆商店的位置。来自 Fairfax(费尔法克斯)的玻璃底片档案,https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-162357694/view。

诺曼·比彻姆 (右) 和他的儿子Ross「罗斯」(左)。诺曼于佐治(乔治)街 105 号经营 Beacham & Sons「比彻姆父子商店」。照片由Wendy Pickering「温蒂·皮克林」提供。威廉·比彻姆没有存世照片。

位于巴打士的华人烟草種植园。照片由 John Henry Harvey「约翰·亨利·哈威」(1855-1938)拍摄,由维多利亚州立图书馆提供。该地点经确认为靠近 Abercrombie House「阿伯克朗比庄园」的 Mt Pleasant「普莱森特山/ 欢乐山」。

Attribution for translation:

温楚良(Aaron Wan)先生翻译,林雍坣(Ely Finch)先生提供中文旧地名等。

巴打士的華人 – 威廉·比徹姆

從 1850 年代到 1950 年代,由 Howick 街到 Rankin 街,再到 Durham 街,該範圍稱為唐人街,那裡有商店、住宅和供菜農租用的房間,這些菜農週末會把蔬菜運到鎮裏出售。華人比徹姆的商店位於佐治(George)街 105 號(即 Bolam Centre 角落) ,店主威廉·比徹姆(William Beacham,中文名字不詳)1835 年出生於大清國廈門府一帶。1853 年比徹姆以 17歲之齡,乘坐 Royal Saxon「皇家撒克遜號」抵達 Port Jackson(傑克森港,即悉尼港)。當時,船上有 304 名由羅伯特·唐斯(Robert Towns)從廈門載運前來的勞工,比徹姆就是其中一人。及後有 44 人調派到 Western Goldfields(西部金礦區)替 Colonial Gold Company「殖民地金礦公司」工作,比徹姆很可能身居其列。比徹姆於 1858 年在索法拉(舊名「都崙埠」)做金礦工,後來又在那裡開店鋪、做翻譯。1864 年,他與 Agnes Fanning「阿格尼絲·范寧」結婚,在她去世後,便帶著女兒 Margaret「瑪格麗特」遷往巴打士。1883 年,比徹姆與 Honora Johnston「霍娜拉·約翰斯頓」結婚,夫婦育有五個孩子。威廉·比徹姆和霍娜拉兩人的關係正好說明,儘管當時與華人男性交往或者帶有種族主義的恥辱感,但是華人男性與歐洲女性之間並非沒有恩愛相守的例子。

比徹姆於 1884 年獲選入巴打士醫院委員會。他在 1885 年和 1895 年憑藉自己飼養的肥豬以及種植的煙草和蔬菜,在巴打士農展會上贏得了一些獎項。比徹姆除了經營商店外,還同時在巴打士擔任了 40 年的華人法庭翻譯員,廣受當地社群尊重和愛戴,另一方面,儘管他的母語是閩南語,而當地大多數人說的是粵語,但他們都十分讚賞其翻譯技能。

1891年,當地報紙《National Advocate》刊登了一封據稱是一名歐洲婦女撰寫,講述自己曾被關押在巴打士一個鴉片窩中的信件後,比徹姆公開為華人社區辯護。他在《給編輯的信》中宣稱:

那封信件和那篇文章從頭到尾都是虛假的。該區婦女我都認識,那個所謂涉事的女人根本不存在。我還必須指出,這篇文章對我全體同胞構成了嚴重的誹謗。

威廉·比徹姆曾於 1872 年入籍成為英國公民,他經歷了契約勞工時代、淘金潮、華人菜園的興起以及白澳政策的推行。1909 年比徹姆去世後,他的么子 Norman「諾曼」接手經營其商店,首先是水果店,後改為煙草店,一直經營至 1929 年。諾曼於 1913 年與 Emily Jones「艾米莉·鍾斯」結婚,但他們從不向孩子透露家族成員帶有華人血統一事。這個事實後來由比徹姆的曾孫女 Wendy Pickering「溫蒂·皮克林」和其他家人所發現。

資料來源:Juanita Kwok(郭思恩博士), 2019, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, PhD thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

鳥修威省(新南威爾士州)巴打士的鳥瞰圖。攝於 1933 年 6 月 9 號,顯示了比徹姆商店的位置。來自 Fairfax(費爾法克斯)的玻璃底片檔案,https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-162357694/view。

諾曼·比徹姆 (右) 和他的兒子Ross「羅斯」(左)。諾曼於佐治(喬治)街 105 號經營 Beacham & Sons「比徹姆父子商店」。照片由Wendy Pickering「溫蒂·皮克林」提供。威廉·比徹姆沒有存世照片。

位於巴打士的華人煙草種植園。照片由 John Henry Harvey「約翰·亨利·哈威」(1855-1938)拍攝,由維多利亞州立圖書館提供。該地點經確認為靠近 Abercrombie House「阿伯克朗比莊園」的 Mt Pleasant「普萊森特山/ 歡樂山」。

Attribution for translation:

溫楚良(Aaron Wan)先生翻譯,林雍坣(Ely Finch)先生提供中文舊地名等。

Early Journeys Over Songlines

Most highways and major roads in Australia follow the Songlines and pathways that Aboriginal people originally used to cross the continent.

Songlines form part of the First People’s oral histories. They can be thought of as oral maps that traverse Country and identify

important places for ceremony, family and resources. These points of interest are memorised through song to guide travellers. Songlines that have survived colonisation remain to be amongst the oldest recorded oral history stories in the world.

There are Songlines throughout what is now known as the Blue Mountains that are used to access the Bathurst region today. The routes generally follow the Songlines used by many First Nations groups. Up to 10 First Nations groups are responsible for the knowledge about these Songlines.

Songlines are not just used for walking; their use has a purpose. Songlines are imbedded with messages that direct people to rich locations for food such as the Wiradjuri area between the foothills of the Blue Mountains and Kelso, and the Dharug area where people of the Galari clan trekked to access seafood feasts and ceremonies. The Songlines can also be used for trade and other ceremonies along the way.

Not one of the ten or more First Nations who traverse common grounds have ownership over the busy thoroughfare through the Blue Mountains area. The many Nations are caretakers of this shared Country.

In the early period of Australia’s colonisation, written history highlights the trouble that colonists had with passing over the formidable Blue Mountains. Accounts show that numerous attempts were made to overcome the mountains by following watercourses which only lead them to impassable waterfalls.

Written texts do not specifically state the reason why the mountains were finally able to be surpassed. One text states that Aboriginal People were not encountered however their presence was known (Read 1988). We know from oral histories that ten or more First Nations travel across the mountains so it’s unlikely that they were not encountered. It is probable that the only way that the route was ‘discovered’ by colonists was by following behind the pathways originally set out by First Nations who regularly travelled these Songlines.

As history is written, in 1813 Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson began their expedition over the mountains by hatching an ‘original plan’ to follow the ridges instead of watercourses (Barker 1992). Using this method, the colonists breached the previously impassable mountain Country and reached as far as the junction of two streams now known as Cox’s River and Lowther Creek, west of Hartley. There, the trio came upon a Wiradjuri camp which had very recently been abandoned. They returned to Sydney to inform Evans of the route, leading to Evans discovering Bathurst.

References

Barker, T 1992, A History of Bathurst Volume 1 The Early Settlement to 1862, published by Colorcraft Ltd, Hong Kong

Read, P 1988, A Hundred Years War: The Wiradjuri people and the state, Australian National University Press, Canberra.

Songlines and Stories in Bathurst

Throughout Bathurst there are many significant and sacred Wiradjuri cultural areas. Most of the colonial era civic or significant buildings have been built on and in their place.

Oral history tells us that there is a cave system beneath the Bathurst Courthouse and the Council building. The cave system was used for Wiradjuri war ceremonies. Close to this location stands the Bathurst War Memorial Carillon.

Underneath the Catholic Cathedral is a place of silent reflection. Today, there is a Wiradjuri yarning circle in the courtyard garden to honour this sacred space.

Two ceremony circles also lie underneath the Town Square that you stand on now.

These Wiradjuri cultural areas are connected by songlines between Wambuul (Macquarie River) and Wahluu (Mount Panorama). William Street generally follows the same course of the Sacred Songline of Wahluu that young Wiradjuri boys use in a ceremonial rite of passage to become initiated men to warriors. Along their journey, the boys have the opportunity to stop at multiple ceremony circles and places of reflection where they can decide whether they are ready.

Only those who feel that they are ready to become men will progress to the final preparation area. This requires passing through the area that is now occupied by the Charles Sturt University campus. Today, universities are considered to be the final stage of schooling. It is in the same general area that the Wiradjuri boys make their final decision to go to Wahluu.

Those who are ready walk with the women around the side of Wahluu to the women’s site. From there, the boys go to the men’s initiation area where they face challenges to become men and are taught essential life skills like making boomerangs and spears. Then, when the men have completed their rites of passage, the men and women come together for a celebration.

Every year, the Bathurst 1000 echoes this rite of passage in non-indigenous culture. The Bathurst 1000 Transporter and Driver Parade uses William Street to slowly shuttle champions of racing to Mount Panorama, following generally the same route as the Sacred Songline of Wahluu. On Wahluu, the best drivers challenge each other on the internationally famous Mount Panorama Racing Circuit, just like the Wiradjuri boys challenge each other, brother vs brother, mate vs mate.